19th century martial arts have long been the poor relations of more popular historical martial arts branches, but in recent days, they have gained more and more recognition. English martial arts are still the most studied from this time period, the numerous and simple sources, the spread of the English language worldwide and the popularity of Victorian culture have greatly contributed to their current status. Singlestick is one of them. This peculiar relative to saber fencing was very popular in Georgian England before being converted to a wooden training tool. This interest has led many people to consider any mention of singlestick in books or newspapers as the British game. A famous instance is the one of Theodore Roosevelt, allegedly a famous American singlestick practitioner… but was he really practicing the old rustic game of singlestick?

| The “Old Game” as described by Allanson-Winn |

Singlestick was practiced since at least the 17th century, some people suggested it was a relative to more ancient practices in fencing schools, but no solid proof can attest to this link. Although it is often associated with England, we forget that other countries were also fond of fighting with wooden swords, as unknown to many the practice was alive in other countries. In France, the practice of “behourder” a derivative of the noble “bohourt” tourneys was practiced very much like singlestick. The first and second Sundays of Lent was reserved for the peasants and bourgeois to fight with sticks and staves. It fell out of practice around the 18th century, but Diderot in his Encyclopaedia noted that the English were continuing this tradition as well as the Spanish who call it “cannas” and the Florentine who call it “bagordare”.

The Victorian version of singlestick was much more in line with what was done in France at the time |

France continued to use singlesticks all through the 18th and 19th century mostly as a fencing instrument for the military saber. While some teachers like de St. Martin (1804) hated the wooden sword, some as Brunet (1884) found it useful to safely instruct beginners and develop sufficient arm strength and control before moving on with the steel sabers. British singlestick seems to have seen the same development in the mid 19th century, slowly transitioning from a vernacular game into military and upper-class fencing.

Mentions of singlestick in 19th century newspapers lead some researchers to point out how popular the old English game was all over Europe and the Americas. The president Theodore Roosevelt himself being the most flamboyant figure of this hobby, but a careful look at the sources seems to indicate that things are not quite what they seem. Here is for example, what Capt. Alfred Hutton had to say about the singlestick in an entry of the Encyclopaedia of sport (1897):

“This old style of “cudgelling” is now quite extinct and the “singlestick” of to-day is mainly a medium for learning the management of the light sabre as it appears in our modern fencing rooms.”

Hutton also describes it as a poor substitute to the sabre for which many calls to its abolition, but he also says that it is an “honest, manly old English sport which should rather be encouraged rather than be allowed to sink into oblivion”.

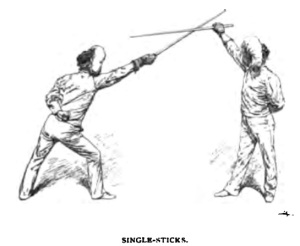

Let’s first define a couple of terms. The term singlestick will firstly designate the British sport in its various incarnations while fencing stick will describe the wooden stick –be it French, British or other- equipped with a wicker or leather handguard. As you will see in this article, I believe that such a terminology should be used in the future to avoid further confusion.

Fencing sticks as sold by Spalding in 1915

While mentions of singlestick in Britain seem to refer mostly to the sport – and even then careful research should be undertaken to establish this fact- most American sources refer to something else entirely when they discuss singlestick; quite possibly French La canne.

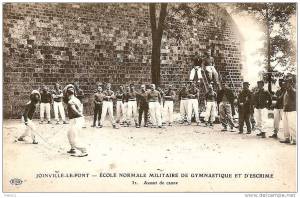

France in the 19th century was a military colossus and a model for any army aspiring to modernize its equipment and tactics. Still gleaming with Napoleonic aura, the nation also had a great reputation as far as fencing was concerned, and many French teachers instructed both civilians and military alike in different countries such as Japan or the United States. Their involvement in the Crimean War showed many countries the need to reform their military. Although the Franco-Prussian war dealt a severe blow to this reputation, the French military doubled with the Joinville school of gymnastic and fencing. The school was operating on a scale never before seen, and pioneered many new methods of exercise and teaching that are still used today. It produced a vast amount of fencing masters skilled in foil, sabre, bayonet, le baton and of course la canne. After their military service, many of them chose to immigrate in order to continue their teaching career. Including, of course, the United States.

A cane “assaut” in Joinville academy, where a lot of Franco-American instructors were taught

It was then only a logical thing that a country with close military ties to France such as the United States sought instruction in the fashionable art of fencing with a cane, but journalists in America, it seems, were not quite sure what to call it. While the word “cane” was sometimes used, most chose to refer to it as singlestick. In fact, the term was used so liberally that even kendo ended up being called “Japanese singlestick” or even –in a manner which couldn’t better transcribe the confusion at this time- “Japanese quarterstaff”. Mentions of French fencing masters teaching singlestick in America abound, and it would be highly surprising that these teachers somehow taught the English game.

Canne Royale as taught in New York in 1898 by Mr. Louis |

| Professor Tronchet from San Francisco’s Olympic Club |

Here are some examples found across American newspapers: Captain Hyppolite Nicolas at the New York Fencing Club, Tromelle, Girard, Cassie, Boulet and Tranque in Boston, Tronchet in San Francisco or Thomas, Tranque, Simon, Dupare, Boulet, de Janon and Gelas in West Point. These are only some of the French fencing masters, as many other teachers of various origins can be found.

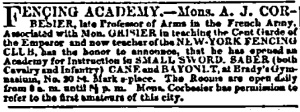

French cane is not the only thing been taught in America at the time. A close parent, Canne Royale from Belgium, is also popular. A certain Mr. Louis was teaching it in New York with his son around 1898 for example (Muskegon Chronicle, sept 14th, 1898), but the Belgian cane became known thanks to a legendary figure in American fencing: Antoine J. Corbesier, who was born in 1837 and served for a while in the Belgian and French army before finding employment at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis.

Belgians along with Italians and French seemed to have been a popular choice at the time for potential masters at arms. The Potomac army allegedly had another Belgian as its instructor general during the Civil War: Captain Arthur de Pelgrom who later taught in Centralia Illinois not only foil and saber but also Mexican dagger, double stick and cane (Centralia Sentinel, December 14, 1865).

Corbesier is often credited with bringing singlestick to the United States, where the art was supposedly unknown at the time. Two questions spring to mind when considering this assertion. Why would a Belgian fencing master bring to the US a British practice? The answer lies further.

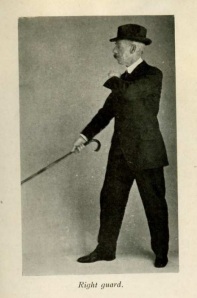

In 1906, a personal student of Corbesier, Andrew Chase Cunningham, wrote a small book on the use of a cane as a weapon of self-defense. His book included many photographs, some of them very telling as to the inspiration for his method.

Cunningham Right guard and a classical Canne Royale guard

His main guards are reminiscent of what can be found in earlier Canne Royale manuals. The comparison between the two leaves few doubts. Add to this an article in the New York Herald in 1886 (june 9th) where it is said that Corbesier had his students practice the “stick exercice” which was “a mode of defense and attack with sticks in unison”. This sounds remarkably like a description of a Canne Royale lesson, where the pupils trained a series of movements in groups sometimes with accompanying music. Finally, before even going to teach in Annapolis, Corbesier taught at the New York fencing club where in 1863 it is said that he taught smallsword, saber, bayonet and cane (New York Tribune, October 19th). No mention of singlestick is made until 1904 when it is said that British singlestick, quarterstaff, judo and Japanese fencing were be introduced to the academy (Springfield Republican, December 17th). It is unclear how long singlestick was taught there, judo, for example, was only taught for a year. Taking all these elements together, it doesn’t seem exaggerated to consider that what Corbesier first brought to the US was not the British version of singlestick, but rather Canne Royale, the monarchical reference being dropped out. In his 40 years of teaching at Annapolis, Corbesier taught this art to about 6000 pupils.

In 1904 St. Louis hosted the Olympic Games. Included in the fencing program was not just foil or saber but also singlestick. Many people then came to believe that British singlestick was indeed an Olympic event. Again the mistake is to consider that singlestick automatically refers to the old British game, and when we look further we find it is very unlikely.

The winner of the event – out of only three contestants- was a certain Albertson Van Zo Post from New York’s Fencing Club. Van Zo Post is often said to represent Cuba, but although he was most likely from the Cuban island, he was really representing the USA. At the time, the Club was headed by a French maître d’armes named Vauthier (Muskegon Chronicle, February 5th 1904). Mr. Vauthier, a Parisian, learned his trade in the military at

This is the only text mentioning Corbesier’s involvement with Napoleon III’s army. Perhaps following the change of government in 1870, it became preferable to avoid the subject |

the Joinville academy where La Canne and Le baton were taught, and later became headmaster of fencing at West Point. Fencing sticks were indeed used to teach sabre to beginners, but no sources indicate that championships were disputed in France, or that the sticks were used at any point when steel sabers could be used, or that this was a seperate branch of fencing at all.

Now, you might ask: then why didn’t France win any medal, or was even represented in those games? Well, the Olympic Games were not what they are today, a dozen countries were represented, and only one French athlete showed up, and to compete in the marathon of all things. The games were mostly a side attraction to the World Fair.

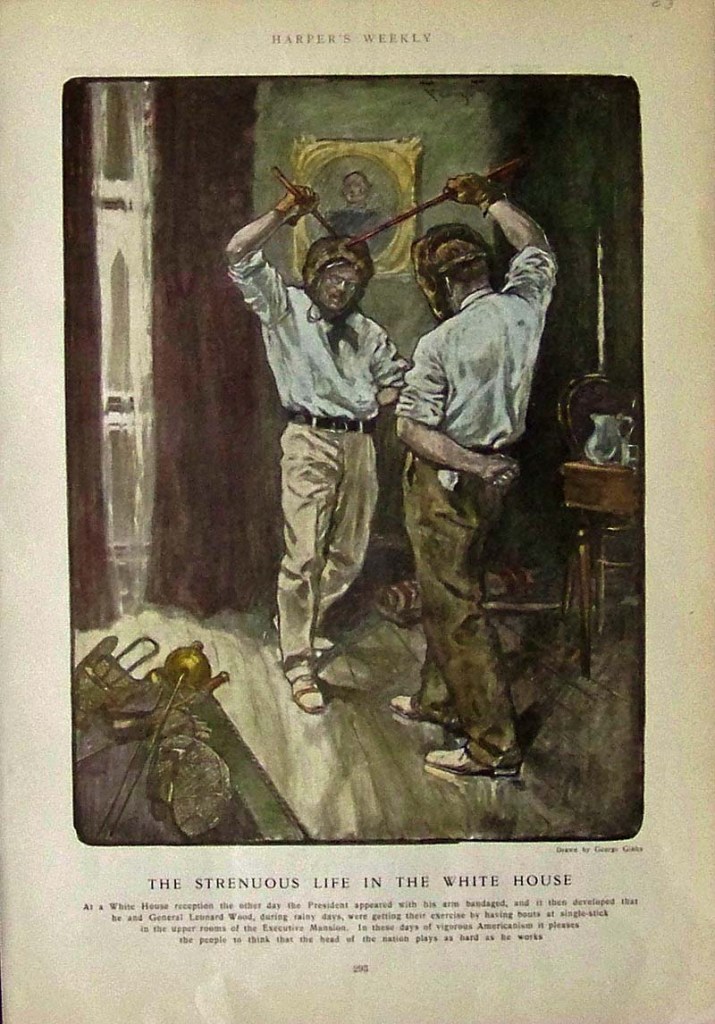

| Roosevelt and Wood practicing “singlestick”. Harper’s Weekly, 1903 |

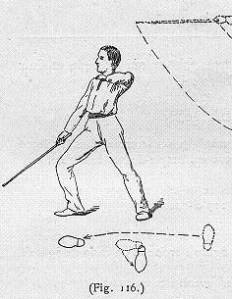

But the most telling case is that of Theodore Roosevelt, who at the time of his presidency was known for practicing singlestick in the White House with General Wood. On one famous incident, Roosevelt got his hand badly bruised, putting him out of training for a while. Few authors have put in question the fact that the president was practicing a form of saber fencing with a stick… but was he really? Again several clues lead us to believe otherwise.

Firstly, let’s observe the picture of Roosevelt and Wood fighting above. One detail immediately jumps out: if they are indeed practicing sabre with sticks, why are there no baskets on these sticks? Fencing sticks at the time being mostly recognized as a cheap alternative to a metal sabre; surely Roosevelt had access to better equipment. And even then why no basket, which undoubtedly lead to his wounded hand? Surely he could have bought baskets along with the sticks? But maybe they didn’t have any on hand at that time. We have to dig deeper to get the real story.

An article mentions that Wood and Roosevelt were at the time both privately instructed in “fencing and singlestick” by Maître François Darrieulat, a French fencing master, instructed in the French army and the Paris fencing academy, of the Washington Fencing Club and also a teacher at Annapolis Academy (Philadelphia Enquirer, October 19th, 1903). A picture of the club taken after 1914 shows some fencing-sticks on the wall along with bayonets and a kendo armor. Again are we seeing here a tool for the sport of British singlestick or a wooden practice sword? The Washington fencers often organized friendly competitions with the Annapolis cadets, which included according to the reporters “singlestick” (Baltimore American, April 22nd 1903). Now we know for a fact that singlestick only arrived at the Academy in 1905, and that cane was taught there for decades. So the Annapolis students could not be competing in the old game at that time.

Darieulat and students of the Washington Fencing Club somewhere after 1914. Library of Congress

Finally, an article comes and muddies the singlestick trail even more. In 1903, Mr. Jean-Marie Gelas and his family moved from France to America to teach fencing, savate, and Jiu-Jitsu. Gelas and his sons were both trained at the French military academy of Joinville-Le-Pont. Quickly acquiring

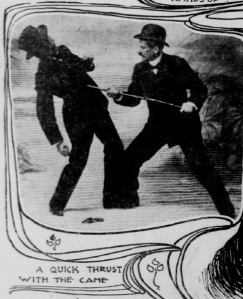

Singlestick at the New York Fencing Club, but what is really illustrated is La Canne |

quite a reputation, Mr. Gelas became a fencing instructor at West Point Academy, but before doing so, he helped publish an article describing what the president is practicing exactly as many people seemed to ignore it. Of course what they demonstrated was classical La Canne, and again all this points toward the strong possibility that what Roosevelt was really practicing was the French art of cane fighting and, if nothing else, that the term was used very loosely to describe any stick fighting activity (Boston Journal, March 8th, 1903).

A hand colored print from Leslie’s Weekly, March 30th 1905, showing two students of Annapolis fencing with canes.

To conclude, can we say that singlestick was unknown 19th century America? No. Can we say that every mention of singlestick in contemporary newspapers is La Canne? No. What is important to understand is that, while our modern world is obsessed with correct typology, and doesn’t tolerate vague terminology, it wasn’t always the case. For many people in the past, an activity where two or more people fought with sticks was known as singlestick, details were best left to the experts. Researchers should then ask themselves when stumbling unto this word in an old publication if it is really the Old British Game or some other form of stick combat.

Update: Thomas Crawley sent me another source which once again confirms the nature of singlestick in America (and maybe elsewhere). The famous Thomas H. Monstery wrote in the New York Athletic Club rules of 1878 what he thought about the use of the term: “I would here remark that the name “singlestick” for the exercise described in the law should be changed to “walking-stick”, “cane-play” or “cudgel play”. The English singlestick is only employed as a cheap substitute for the sabre or broadsword in practice (…).”

There have been several different types of stick fighting methods in the British Isles over the centuries. These included: Singlestick; Cudgelling; Backswording (sometimes also fought using real blades with dulled edges); Waster play; Bavins and, of course, Quarterstaffing.

In Singlestick alone, the rules of ‘play’ varied at different times, and in different parts of the country. Sometimes the free hand would simply be held loosely behind the back. Sometimes that hand would be tied tightly against the rear leg thigh. At other times the free hand would be required to hold onto a belt, neckerchief or scarf (etc) tied loosely around that thigh. It didn’t matter what method was used, the free hand was not supposed to play any part in the contest.

Competitors sometimes travelled far and wide in order to participate in the various competitions. They were often known as Gamesters. The events usually took place during local Veasts and Festivals. By travelling around in this manner, high level and Champion stick fighters could make good money.

In order to show that they were willing to enter the tournament, Gamesters would remove their hats and toss them into the ring. Yes, that’s where the saying comes from. The sticks were around 34 inches long, sometimes longer. They were usually cut from Ash (although Hazel or even rattan was also used in some areas), and they were left overnight to soak in water. This kept the sticks pliable, and helped prevent them from splintering.

The only protection afforded to the Gamesters was a ‘pot’, or small basket hilt, woven from thin sticks or cane (as used for basketry). Practise hilts were later sometimes made from thick cowhide (leather). In some areas they also allowed Gamesters to wear a leather jerkin. The arms were always bare, however. Oh yes, there was one other means of protection, especially in the West Country, the little prayer, ‘God spare our eyes’.

In many such contests, all blows were allowed, and to all parts of the body, except thrusting with the point. The contest was only won, however, when first blood was drawn above the jaw-line. Knocking an opponent’s teeth out (or even an eye) was not unknown. Splitting the forehead with the tip was, perhaps, a little more common. If competitors fought too close it was not always easy to draw blood. Sometimes fights went on for an hour, or even two, without blood being drawn above the jaw-line. It was not unknown for men to drop exhausted, and to even die, following such a gruesome contest.

The high overhead semi-hanging guard was common, with fast ‘abaniko’-like hits delivered at such speed that it was said to sound like a boy running along with his stick held against a set of iron railings.

At the end of each bout, the ‘pot’ would be slid from the stick and passed around the crowd. Spectators would then put nobbins (coins) into the pot to be presented to the winner. So in other words, Gamesters fought for the pot. It was not uncommon for the winner to also receive a new hat as well.

Later on in some parts of the country, stick play became a cheap and nasty substitute for fencing with real blades. The old-country methods of fighting was, however, never meant to be anything other than a contest with sticks.

A very good resume of the sport Mr. Batts. Although it does seem that arms were sometimes protected.

http://www.flickr.com/photos/shepton_bloke/7183970922/

Probably a bit of artistic licence. The rules generally didn’t allow it.

“It is the same in single-stick. If you are not spared too much, and are not too securely padded, you will, once the ash-plant has curled once or twice round your thighs, acquire a guard so instinctively accurate, so marvellously quick, that you will yourself be delighted at your cheaply-bought dexterity. The old English players used no pads and no masks, but, instead, took off their coats, and put up their elbows to shield one side of their heads.” Phillipps-Wolley

I must respectfully disagree, as it is quite a big artistic license to add an equipment that wasn’t there and I see no reason for doing it. Keep in mind that there was no governing body and no universal rules to these events. If they agreed to wear some kind of protection nobody would have stopped them and I think that’s what happened in this case. Hutton also talks about face masks which leave the top of the head uncovered but protect the face. Was it common? Probably not. Was it possible? Most likely.

Prior to the internet, I spent more than eight years researching old books, documents and manuscripts in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and the University Library in Cambridge, and I can assure you that according to everything I read, padding of any kind was generally frowned upon in rural Singlestick and Cudgelling matches. Sleeveless leather jerkins were often worn and, as I mentioned already, the non-weapon hand and arm was often tied down, or otherwise limited in use by holding onto a belt, or neckerchief tied losely around the thigh. The target was the head, and the object of ‘the Game’ (hence the term ‘Gamesters’) was to draw blood above the jawline, so that the blood ran down ‘one inch’. Without going to the trouble of going through all my files to check, I believe that when you refer to Hutton and face masks, that was because we’re now talking about the method that was a cheap-and-nasty substitute to Fencing with live steel blades. Whereas the rustic version practised at Veasts and other such events was what I was really talking about.

No I am actually referring of the entry he wrote on singlestick in the Encyclopaedia of sport in 1897 in which he describes and even provides an illustration of what he calls a “demi-mask” which he says was not generally worn but was sometimes used to protect the face while leaving the top of the head unprotected. I absolutely do not call into question your expertise but I think that it is very difficult to deal in absolutes in the field of history.

Here is the entry in question: https://archive.org/stream/encyclopaediaofs02suff#page/360/mode/2up/search/singlestick

We are not really in dispute in with one another my friend. Different forms of contests took place, at different times and places throughout the country. As you quite rightly say, the version(s) of Singlestick that were a substitute for practice with a bladed weapon, did indeed allow greater protection than the rustic Singlestick matches to which I was mainly referring to.

Those later versions, that I would describe as being a cheap and rather poor alternative to fighting with steel blades, were quite different from the earlier rural, or rustic versions or stick fighting. These versions were also known by a variety of names, depending on time period and/or part of the country. Names such as: ‘Backswording’, ‘Cudgelling’, and ‘Singlestick’, being common. Although, just to confuse matters further, the term ‘Backswording’ was also used by some who fought one another on stage with blunt-edged real steel swords.

In those old versions of Singlestick, a.k.a. ‘Backswording’ or ‘Cudgelling’ contests, people such as ‘Blackford the Butcher’, from the village of Purton in Wiltshire, used to travel far and wide in order to compete [very successfully] in those early and rustic forms of combat.

Those contests were not in any way ‘martial arts’, however, they were simply two men trying to knock lumps out of one another with sticks! No more, no less. But there was obviously skill required, in order for people such as Mr Blackford to consistently defeat most of those he met in such contests.

Well unless I am misunderstanding you we both have different ideas. I am saying that equipment was present, although in a limited way, when people played the rustic game. You say that equipment was only introduced when the game changed to a more fencing like approach.

But here is my main point: Both Hutton and the painting refer to the rustic game, not to the new practice (of which I make a clear distinction in my article). Hutton makes it clear that the mask was worn during that period, and the painting makes absolutely no doubt as to what it is portraying. Again was this common? Probably not and the mask was probably a later development in the game, but with those two elements we can hardly say it wasn’t done.

You said: “No I am actually referring of the entry he wrote on singlestick in the Encyclopaedia of sport in 1897 in which he describes and even provides an illustration of what he calls a “demi-mask” which he says was not generally worn but was sometimes used to protect the face while leaving the top of the head unprotected.” Which may well have been the sort of thing you might expect to find in the kind of places familiar to Hutton.

But I very much doubt that he spent too much of his time attending rustic events, and mixing with common people, being as he was an Officer in the King’s Dragoon Guard! In any case, he was far more familiar with the use of real swords than he was with stick-fighting.

But all that aside, I was referring to the sorts of ‘Singlestick’ contests that were going on 3/4 century before that, in any case. Which was before Hutton was even born too! There’s an eye-witness account of such a contest that took place in 1820. It was written to the Editor of the Every-Day Book, dated on October 20, 1826, although it has the date November 15 above it. The title of the submission is: Hungerford Revel, Wilts. You should be able to locate it with a Google search, if not, I could always copy it from my notes.

And in case you’re interested, I can tell you that the old Army & Navy stores in London were still selling sticks and stick hilts (basket and hide) at least until 1935-6 at least. I suspect they stopped when the Second World War broke out, but that is only a supposition!

Oh of course apart from the arm padding I don’t think those masks were in use around the early 19th century, after all they were barely used in regular fencing! Probably much more around the last few decades of the rustic game.

Pleasure discussing with you!

Likewise my friend.

Reblogged this on The Obsession Engine and commented:

Here’s an article on the singlestick.

My lovely wife and I have been watching the Sherlock Holmes-inspired Elementary series, and he’s seen occasionally working his singlestick moves on a BOB dummy in his home.